Time Out perfected the city listings magazine

For 50 years, Tony Elliott’s Time Out magazine was a fixture on London’s news-stands. It did not invent the concept of the events and entertainment listings weekly, but perfected the format. Expansion saw spin-offs and editions launched in other British cities and across the world. There were several attempts to challenge its dominance, including City Limits and Richard Branson’s Event magazine. Time Out saw them all off. However, it was brought down by online competition, becoming a freesheet and dropping most of its listings in 2012, and closing in 2022. Elliott was awarded a CBE for services to publishing in 2017 and died three years later. The Time Out website was still published in 2024 with the tagline ‘Discover the world’s coolest cities.’ |

|

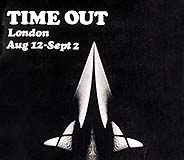

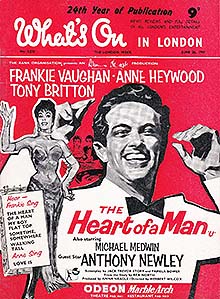

| What's On in London from June 1959 with a Frankie Vaughan cover for the film Heart of a Man | Cover of Time Out's first issue dated 1968 September 2. Bob Harris and Tony Elliott were the joint editors |

A child of the underground

London has rarely been short of weekly magazines devoted to its events, culture and nightlife. Among the many titles have been London Mail (1912-26), London Life (1920-60), Piccadilly (1926-29), What’s On in London (1934-77), London Off Duty (1946), Show Business & What’s Doing in London (1950), London Life (Tatler relaunch, 1965-66), London Look (1967), Look of London (1967), and The Londoner (1968).London Life was a relaunch of Tatler as a weekly listings magazine under editor Mark Boxer, who had made his name launching the colour supplement at the Sunday Times for Lord Thomson. London Life was very much for the Swinging Sixties smart set, of which Boxer was himself a member. His team included David Hillman and David Puttnam, with Jean Shrimpton as a consultant fashion editor and photographers such as Terence Donovan, Duffy and Ron Traeger. The first issue was in October 1965 but it closed at Christmas 1966. At 2/6, it was expensive – five times the price of the Radio Times – and a very upmarket failure. So, when Tony Elliott was working on his new magazine in 1968, there were just two rivals around: What’s On in London and the Londoner, a renamed version of the features-focused Look of London. The latter was another product of the Swinging Sixties. In his autobiography, Diary of a Teddy Boy, Mim Scala describes how, along with Sir William Pigott-Brown, he had taken over the name London Life and changed the name to Look of London. Pigott-Brown, nicknamed the ‘sporting baronet’, was an Old Etonian who had inherited a fortune and spent the rest of his life spending it, as a man-about-town and racing enthusiast.

What’s On in London was a traditional listings weekly, focusing on ‘news, views and notes about all of London’s entertainments’, according to its covers in 1948. The covers usually advertised the latest film and a West End cinema. It was a straightforward guide to commercial entertainment for visitors to the capital.Time Out cost a shilling when it hit the streets in August 1968. However, there was little comparison to its potential rivals: it was not weekly, did not use a magazine format, focused on listings rather than features, and was a left-wing agitprop magazine. Time Out had more in common with underground magazines such as Oz or International Times . It was formulated by Tony Elliott (aged 21) with Bob Harris (aged 22). Elliott was studying French at Keele University, and the magazine was nearly called Where It's At . Harris gained fame as ‘Whispering Bob’ presenting BBC TV’s Old Grey Whistle Test from 1972 (the series was cancelled in 1987 by Janet Street-Porter, who was head of youth programmes, and was divorced from Elliott). The early issues were a folded sheet and various estimates put the first issue sales at 3,500-5,000 copies. A second issue followed three weeks later. It became an A5 fortnightly before going weekly as an A4 magazine in 1970.

The first issue consisted of a single sheet that folded down to 16 A5 pages. The cover was what looked like a computer-generated abstract line image with the text Time Out, London, the date (Aug 12-Sept 2) and the price (1s). The back page showed a crude interpretation of Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man along with a brief description of the magazine’s strategy:Information on time out in London has, until now, been either scattered in different forms, through several magazines & newspapers, or crammed non-objectively into booklets & magazines, which do tell you where to go but don’t tell you how, why, or what to expect when you get there.

We have tried to make our information as comprehensive as possible but at the same time we have been very selective, in so much as the places we list are the places we think are worth your attention.The page invited people to send their information in about events and gave a copy date of August 21 for an issue to be published seven days later covering the period Sept 2-23.

It was published by Elliott-Harris Publications at 7 Southampton St in Covent Garden. This was next door to Tower House, the offices of George Newnes, publishers of magazines such as Nova, Tit-Bits and Woman’s Own. Time Out was typeset by Big O Press at 49 Kensington High St, and printed in Watford by London Caledonia Press.

Events listed included: buildings to explore; an ‘immediate event’, which consisted of two stanzas of Leonard Cohen lyrics ‘for Anne’; classical music; bookshops; ballet; electronic music; jazz; theatre (including the RSC at Stratford-upon-Avon); theatre clubs; puppets; exhibitions; paintings-sculpture; and lectures. The section Marches/Meet the Fuzz, encapsulates the left-wing student attitude of Time Out in its first decade. As it expanded, staff were taken on with a similar background and there was a policy of paying everyone – writers, editor, office cleaners – the same wages. |

|

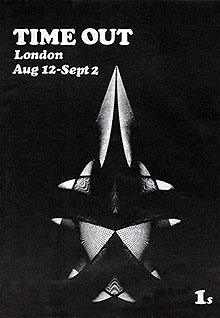

| One of several Time Out covers supporting underground monthly Oz in its 1971 obscenity trial | Frank Zappa portrayed for Time Out by Oz artist Peter Brookes (17 December 1971) |

The format became A4, and there were variations of the masthead until it switched to A4 and classic ‘neon-light’ masthead was designed by Pearce Marchbank. He worked on the magazine at various times from 1970 to 1983, and was appointed a Royal Designer for Industry in 2004.

As befits its left-wing, underground roots, the magazine supported Oz during the infamous 1971 trial, and Peter Brookes, who did many Oz covers and illustrations, did a Time Out cover that year. |

|

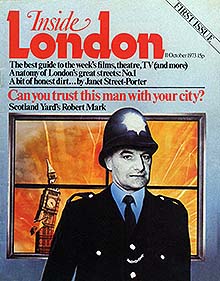

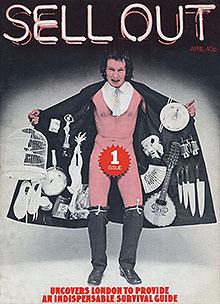

| Inside London launch cover 1973 from Peter Elman, a former editor of advertising trade weekly Campaign | Sell Out's 'flasher' first cover. Janet Street-Porter was the editor, Elliott was the publisher |

Competition and expansion

Inside London was launched in 1973 as a Time Out competitor. The first issue was dated 11 October and cost 15p for 80 pages. The editor and publisher was Peter Elman, a former editor of weekly advertising trade title Campaign. It was modelled on New York Magazine and aimed to provide an ‘intelligent weekly guide to the capital’. The first print run ‘approached’ 100,000 copies. The launch cover was ‘Can you trust this man with your city?’ about the Metropolitan Police commissioner, Robert Mark. However, it failed to succeed. In it, Janet Street-Porter wrote a piece ‘One woman’s London: A bit of honest dirt’.Street-Porter had worked on Petticoat, the Daily Mail and London’s Evening Standard. By 1973 she was co-presenting an LBC radio show with Fleet Street columnist Paul Callan and the following year got together with Elliott to launch Sell Out, ‘an indispensable survival guide’ for Londoners. It was an expanded version of Time Out’s Sell Out section, which listed bargains and carried consumer information.

The cover used spot red but all the other pages were in mono on uncoated paper. The cover matter was a thin card. All the listings in the magazine were free. She was the editor, he was listed above her as the publisher and the company was Best Brands at 374 Gray's Inn Rd. They married the year the magazine came out, but divorced two years later. |

|

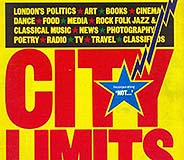

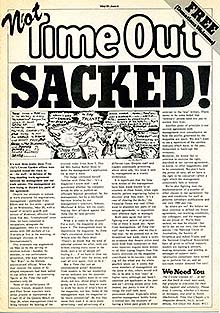

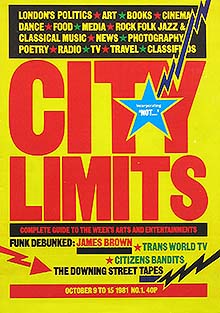

| Not Time Out as an A4 freesheet (May 29). Later issues adopted a tabloid format | City Limits first cover (October 15). Art director was Carol Warren with David King as design consultant |

City Limits – born of internal strife

In April 1981, publication of Time Out was suspended because of a strike over Elliott's decision to end the magazine's policy of the same pay for all staff (a period he has described as 'guerrilla warfare'). Many left to start a protest news sheet called Not Time Out. Not ... became a free, tabloid format newspaper printed by East End Offset. Issue 17 was subtitled 'City Limits minus 4' because by then the staff had raised funding to relaunch in a magazine format. Under the headline 'City Limits out on October 8', the front page splash (alongside a photo of Labour MP Tony Benn reading a copy of the free paper) stated:The new magazine produced by more than forty of the sacked staff of Time Out will be on the street on October 8. ... The cover price for 84 pp will be 40p – 10p cheaper than the old Time Out.The Greater London Council under left-wing leader Ken Livingstone funded the title. So it was ironic that the launch was made possible by legislation brought in by Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government (from issue 18):

Our new company will comply with the Tory government's new Small Business Start-up Scheme. This offers massive tax advantages both to private and business investors.City Limits expected to have a turnover of £1.25 million in its first year.

The cover date of the first issue was October 9-15. The publishing company was London Voice Ltd at 313 Upper Street, Islington, N1. The distributor was New Statesman, the left-wing weekly. It cost 40p for 92 pages. The editor was John Fordham. Not Time Out is referred to in a blue star on the front cover, which says 'Incorporating "NOT...".' The new magazine referred to Time Out as Another London Magazine. The launch issue's editorial states:

Six months, innumerable dismissals, several writs, threats, recriminations, sit-ins, lock-outs and undignified rumbles later, we have brought you City Limits – a paper that we think you'll agree was worth the fight.Cartoonist Steve Bell's Maggie's Farm switched to City Limits with the first outing portraying Norman Tebbit ripping off an interviewer's head on Maggie's order: 'Get him Psycho!'

Art director Carol Warren employed David King as design consultant to establish an immediately recognisable cover style on a low budget. Christopher Wilson interviewed King for a 2003 issue of Eye and described his work so:

His graphic style – an easily recognisable mix of explosive sans serif typography, solid planes of vivid colour and emphatic rules – reworked for the New Left in Britain the graphic language of the Russian Constructivists.King had built up a unique collection of Soviet imagery, which was acquired by the Tate museum in 2016. City Limits was run as a workers’ co-operative and folded in 1993.

|

|

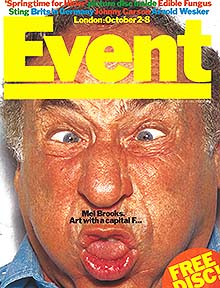

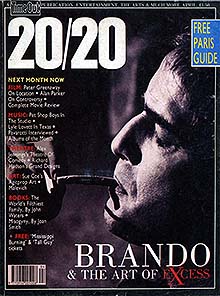

| Branson takes on Elliott: Mel Brooks and Springtime for Hitler on the first issue of Event, 2 October 1981 | Monthly spin-off: 20/20 in April 1989. Note the Time Out branding, which was not used on Sell Out |

Branson’s big Event

Back in 1972, Richard Branson’s business empire was founded with Virgin records to release Tubular Bells by Mike Oldfield. It became a massive hit after being used on the soundtrack of The Exorcist. In 1981, Branson tried to capitalise on the strife at Time Out by launching a competitor, Event. The editors were listed as Al Clark and Pearce Marchbank, who was also the design director. Branson was the publisher. Listings were free, and the magazine had a similar look to Time Out, little surprise given Marchbank’s experience working for Elliott. The first issue cover promoted a four-page interview with Mel Brooks about Springtime for Hitler. Inside was a flexidisc 45rpm single of music from the film.Elliott goes monthly with 20/20

In 1989, Elliott launched 20/20, a monthly review magazine with the Time Out name used as branding on the cover. The editor was Don Atyeo. It closed a year later. Elliott had a bigger challenge on his hands, however; one that would affect all newspapers and magazines.Taking on the BBC and ITV

Elliott had a legal run-in with ITV in the early 1980s over publishing details of programmes. This drove him to seek an end to the monopoly the BBC and the ITV companies had on publishing listings for their programmes in advance, through the Radio Times and TV Times. These were two of the best-selling and most profitable magazines in Britain. At the time, newspapers could only print schedules for the day of publication.Elliott encouraged other publishers to press the government for change, and in February 1991, deregulation of the TV of listings market was achieved. The duopoly of the BBC’s Radio Times and TV Times, which was by then published by IPC, was broken. To prepare for the competition, the BBC had bought contract publisher Redwood and launched a series of TV spin-offs. IPC slashed the cover price of TV Times to move downmarket and launched What’s on TV. Time Out added weekly TV listings. There was a boom in TV-based weeklies. Bauer launched TV Quick. Hamfield launched TV Plus, which soon folded. The change also sparked the expansion of newspaper supplements, particularly Saturday and Sunday editions, which developed their own weekly guides. Other magazines, such as Hello, added listings sections.

Elliott also supported launches by start-up publishers, including Second Generation and Untold (1998). |

|

| This 2003 cover shows the Time Out international branding adopted in London the previous year | Time Out Chicago launch, 3 May 2005: 'The where-to-go, what-to-do weekly' |

Set on world domination

Time Out then set out on a massive programme of international expansion, even as it faced greater competition in the UK from bigger listings sections in newspapers such as the weekly A5 Guide in the Guardian and websites such as the Evening Standard’s This is London from 1998. The Big Issue, a London magazine sold by homeless and long-term unemployed people, was founded by John Bird and Gordon Roddick in September 1991. It cost 50p and 60% of the cover price was kept by the vendor. Editions have been launched in other cities since.Elliott launched Time Out New York in 1995. The expansion continued with Elliott setting up joint publishing companies or licensing the name to publishers in dozens of cities. The website timeout.com was launched in 1998 with the subtitle ‘The world’s living guide’ and sections on 26 cities. By 1999, timeout.com/london had these primary sections: This Month, Accommodation, Sightseeing, Essential Info, Entertainment, Eating & Drinking, Shopping, Kids, Gay & Lesbian, City Links. In March 2002, the title on the London cover was reduced in width with a red bar for the city name to match the international editions.

A quote in an article by Jeremy Grant in the Financial Times (15 March 2005) summed up Elliott’s philosophy. The article discussed the Chicago launch of Time Out and its prospects against the Chicago Reader, a free publication with a circulation of 140,000:Yet Tony Elliott ... believes success will come because he holds that weeklies, such as the Reader, ‘will never cut editorial for listings’. ‘We work very much the other way around’, he says, ‘so we always thought there was a gap (in the market).’Time Out Beirut and Time Out Almaty (Kazakhstan) bought the network to a total of 17 cities in May 2006. Group annual turnover was £20m a year. Other branded products included travel magazines, city guides, and books.

In 2008, the magazine began putting its website address, timeout.com/london, on the cover. Its catchlines at the time included 'London’s weekly listings bible', 'Get inspired by your city' and ‘Know more. Do more.’

The demise of Time Out

The wealth of information in daily and Sunday newspapers reduced the need for listings magazines and City Limits folded in 1993. The prospects for magazines became even worse as online sources expanded, particularly once mobile phones became ubiquitous. Time Out became a freesheet in 2012 and dropped most of its listings, even though its travel guides and tourist books were sponsors of the 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games in London.Elliott was appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in the 2017 birthday honours list for services to publishing.

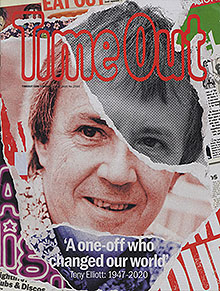

During the Covid-19 pandemic, the magazine was not published. The online version focused on virtual events for people at home during the lockdown. He died in London of lung cancer on 16 July 2020, at the age of 73. Time Out's issue of August 2020, just after the Covid lockdown, marked Elliott's death with a cover and profile inside. |

|

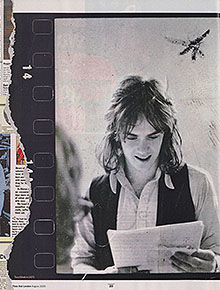

| Time Out marks death of Elliott in its August 2020 issue | Profile inside the issue showed a photograph of Elliott in 1970 |

The last edition of Time Out was dated 23 June 2022. It continues online but is now just a brand, lost in the online miasma.

The first poster-style issue from 1968 can be seen at the Time Out website.